Asset Allocation – What the Research Says

A private investor, paying attention to the debates of the last twenty-five or so years, would have found himself enjoying moments of seeming clarity and enlightenment from the research and academic papers, only to be confounded by their misinterpretation in much of the material targeted to retail markets.

What follows in this article is not a rigorous analysis, but a short overview of some of the academic discussion on portfolio construction.

Markowitz 1952

In 1952, Harry Markowitz published a paper entitled “Portfolio Selection”. Universally accepted as groundbreaking thought, Markowitz’s paper essentially took the common wisdom ‘Don’t put all your eggs in one basket’ and looked at the mathematics and theory behind optimising an investment portfolio.

Markowitz characterised risk as variance of returns (‘V’), the extent to which price volatility introduces uncertainty into anticipated returns (‘E’). Diversification helps reduce portfolio variance, but the returns from securities are too intercorrelated for there to be a portfolio that gives both maximum expected return and minimum variance. There is a rate at which the investor can gain expected return by taking on variance, or reduce variance by giving up expected return. The ‘efficient line’ is the line drawn from the point of minimum variance V to the point of maximum return E, following a set of definite rules.

Markowitz says: “Not only does the E-V hypothesis imply diversification, it implies the ‘right kind’ of diversification for the ‘right reason.’ The adequacy of diversification is not thought by investors to depend solely on the number of different securities held. A portfolio with sixty different railway securities, for example, would not be as well diversified as the same size portfolio with some railroad, some public utility, mining, various sort of manufacturing, etc. The reason is that it is generally more likely for firms within the same industry to do poorly at the same time than for firms in dissimilar industries.”

Markowitz noted that if an investor diversified his money between two portfolios (e.g. two investment companies) that have equal variances, then mathematically the resulting compound portfolio will typically have a variance less than either of the original portfolios (it cannot be more).

But there is a limit to the benefit of increasing diversification. A Markowitz Efficient Portfolio is one where no added diversification can lower the portfolio’s risk for a given return expectation (alternately, no additional expected return can be gained without increasing the risk of the portfolio). The Markowitz Efficient Frontier is the set of all portfolios that will give the highest expected return for each given level of risk.

Markowitz’s paper and his 1959 book “Portfolio Selection: Efficient Diversification of Investments” became a cornerstone of what is known as Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT).

The concepts of efficiency were essential to the development of the Capital Asset Pricing Model, and in 1990 Markowitz together with William Sharpe and Merton Miller received the Nobel Prize in Economics.

BHB 1986

In 1986, G.P.Brinson, L.R.Hood and G.L.Beebower (BHB) published “Determinants of Portfolio Performance”, a 6 page paper that has already spawned 25 years of debate and an Internet full of misunderstandings and misquotes.

BHB used quarterly data from 91 US pension funds and created a framework for analysing portfolio returns. The paper defined investment policy as long-term asset allocation (including asset classes and weights), i.e. the policy identifies the normal portfolio. Policy, timing and security selection each have their own attributable returns. Timing is the strategic under or overweighting of an asset class relative to its normal weight, for purposes of enhanced return and/or risk reduction. Security selection is the active selection of investments within an asset class.

The fateful paragraph from BHB 1986 reads:

“The results are striking. Naturally, the total plan performance explains 100 per cent of itself (Quadrant IV). But the investment policy return in Quadrant I (normal weights and market index returns) explained on average fully 93.6 per cent of the total variation in actual plan return; in particular plans it explained no less than 75.5 per cent and up to 98.6 per cent of total return variation. Returns due to policy and timing added modestly to the explained variance (95.3 per cent), as did policy and security selection (97.8 per cent). Tables 6 and 7 clearly show that total return to a plan is dominated by investment policy decisions. Active management, while important, describes far less of a plan’s returns than investment policy.”

The above has turned into perhaps the most misquoted sentence in financial history, usually along the lines of “90 percentage of portfolio performance is down to asset allocation”. It sounds like a revelation of portfolio design, but is wrong: the results presented by BHB refer to variation in returns over time, not the actual level of return.

The supposed findings of BHB have been perpetuated and misquoted ever since, and still are today even after 25 years and a large body of discussion and debate on the matter (see especially Nuttal, 2000). Many times also, even if the reference to variation is preserved in a quotation, the surrounding text or commentary still draws incorrect conclusions regarding the relative importance of investment policy and active management.

In particular, misquotes and misinterpretations have found their way into vast reams of marketing material from the financial services industry, particularly the indexed funds sector.

From the point of view of a private investor wishing to optimise a portfolio, some considerations include:

- The BHB results state an effect (policy explains more variation than active management) without taking into account the cause (there is no mention of the extent to which the pension funds studied actually practised active management).

- The research does not decompose policy returns and their variation to identify the extent to which those are attributable to the behaviour of the broader market (market returns). A rising tide lifts all boats.

Nevertheless, the closing implications of the BHB paper are useful for further consideration:

“Design of a portfolio involves at least four steps:

- deciding which asset classes to include and which to exclude from the portfolio;

- deciding upon the normal, or long term, weights for each of the asset classes allowed in the portfolio;

- strategically altering the investment mix weights away from normal in an attempt to capture excess returns from short-term fluctuations in asset class prices (market timing); and

- selecting individual securities within an asset class to achieve superior returns relative to that asset class (security selection).

Jahnke 1997

In 1997 W.W.Jahnke published “The Asset Allocation Hoax”, which took BHB 1986 to task in many areas. Jahnke comments: “Unfortunately, both the study’s conclusions and the interpretations of those conclusions are wrong.”

Jahnke pointed out that a typical investor is more interested in the range of possible annualised returns rather than the variance of quarterly returns. According to BHB’s own work: “Another interpretation of the BHB study is that, for the ten-year period covered in their study, asset allocation policy returns explain only 14.6 percent of the range of actual portfolio returns!”

Jahnke also suggested that BHB incorrectly used variance rather than standard deviation to analyse variation. Standard deviation operates in the same units as return. Variance is the square of standard deviation. If analysis is done using the more appropriate standard deviation, the BHB data shows that asset allocation policy explains only 79 percent of the variation of quarterly returns, not 93.6 percent as reported.

Nowhere in the BHB study is cost mentioned. There is no discussion of the extent to which differences in cost – operating expenses, management fees, brokerage commissions and other trading costs – explain the differences in returns. As we know, cost can be a significant factor in long terms returns for an individual investor.

Finally Jahnke rounds on the advice proposed by BHB. They advocate a long term, fixed weight asset allocation policy. However, Jahnke says: “Only if expected returns are fixed should asset allocation weights be fixed. In fact, investment opportunities change over time, both absolutely and relatively.” Historically we have witnessed dramatic shifts in stock and bond market valuations. Internationally, even the riskiness of countries vary, with some economies disappearing altogether and new ones emerging to become fully-fledged developed markets.

Jahnke proposes that asset allocation should be viewed as a dynamic process. It should take into consideration both pension obligations (or, in the case of individual investors, investment goals) and capital market opportunities, including risk. As investor goals and investment opportunities change, asset allocations should also change. “The idea that the most important investment decision should be fixed at some arbitrary point in time is strange advice.”

Ibbotson & Kaplan 2000

In 2000, R.G.Ibbotson and P.D.Kaplan published “Does Asset Allocation Explain 40, 90 or 100 Percent of Performance?” which again revisits the disagreement over the importance of asset allocation policy. Ibbotson looked at 5 years of quarterly pension fund data and also 10 years of monthly returns for 94 US balanced funds in the Morningstar universe, ending March 31, 1998.

Ibbotson & Kaplan said that the debate surrounding the original BHB 1986 paper could be assisted by asking different questions. Ibbotson asked three very specific questions about the importance of asset allocation:

- How much of the variability of returns across time is explained by policy (in other words, how much of a fund’s ups and downs do its policy benchmarks explain)?

- How much of the variation among funds is explained by differences in policy (in other words, how much of the difference between two funds’ performance is a result of their policy difference)?

- What portion of the return level is explained by policy return (in other words, what is the ratio of the policy benchmark return to the fund’s actual return)?

To answer the first question, which is the question BHB addressed, Ibbotson looked at time-series regression of fund returns. The results broadly confirmed the BHB findings (circa 90%), but for the mutual funds were slightly lower than for pension funds, consistent with the notion that pension fund managers as a group are less active than balanced fund managers.

To answer the second question, Ibbotson used cross-sectional analysis to compare funds with each other. Ibbotson noted that “many people mistakenly thought the Brinson studies answered this question.”

If all funds were invested passively under the same asset allocation policy, there would be no variation among funds (yet 100 percent of the variability of returns across time of each fund would be attributable to asset allocation policy). If all funds were invested passively but had a wide range of asset allocation policies, however, all of the variation of returns would be attributable to policy.

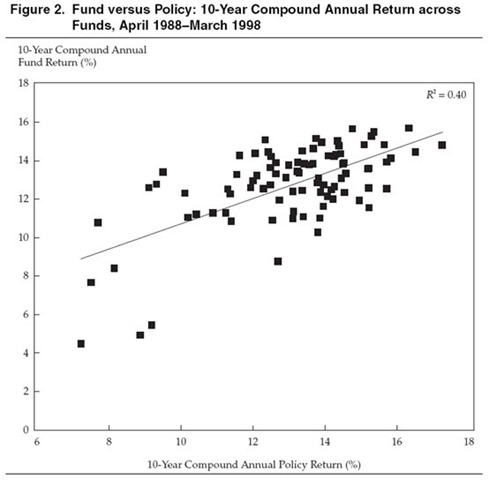

Ibbotson carried out cross-sectional regression of compound annual total returns. The plot below shows the 10-year compound annual fund return against the 10-year compound annual policy return.

The R-squared statistic of this regression showed that for the mutual funds studied, only 40 percent of the return difference was explained by policy. The remaining 60 percent is explained by other factors such as asset-class timing, style within asset classes, security selection, and fees.

For the pension fund sample, the result was only 35 percent, and the variation of returns among funds that was not explained by policy was ascribed to the same factors and to manager selection.

Moving to the third question, Ibbotson also noted: “Many people also mistakenly thought that the Brinson et al. studies were answering what portion of the return level is explained by asset allocation policy return, with an answer indicating nearly 90 percent.”

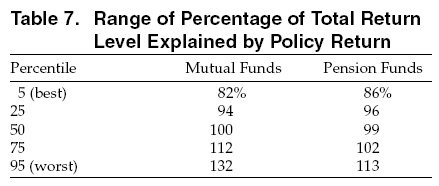

Ibbotson calculated the percentage of fund return explained by policy return for each fund as the ratio of compound annual policy return divided by the compound annual total return. A fund that stayed exactly at its policy mix and invested passively will have a ratio of 1.0 (or 100%), whereas a fund that outperformed its policy will have a ratio less than 1.0. The results for the Ibbotson data are presented below.

Because the aggregation of all investors is the market, the average performance before costs of all investors must equal the performance of the market. Because costs do not net out across investors, the average investor must be underperforming the market on a cost-adjusted basis. The implication is that on average more than 100 percent of the level of fund total return would be expected from policy return; this is confirmed by the results.

Ibbotson & Kaplan comment: “This is not to say that active management is useless. An investor who has the ability to select superior managers before committing funds can earn above-average returns.” In the table above, if 82% of total return for the top percentile of mutual funds is explained by policy return, then 18% must be due to active management factors such as timing and security selection.

In conclusion, Ibbotson says: “Our analysis shows that asset allocation explains about 90 percent of the variability of a fund’s returns over time but it explains only about 40 percent of the variation of returns among funds. Furthermore, on average (my italics) across all funds, asset allocation policy explains a little more than 100 percent of the level of returns.”

Droms 2006

In parallel with the debate over the extent to which asset allocation policy explains returns, has been a wide interest in the extent to which mutual funds exhibit performance persistence. That is, whether a fund’s past performance carries any information on future performance. There has been a great deal of academic research on this subject and a large number of papers published.

In 2006 W.G.Droms published a literature review “Hot Hands, Cold Hands: Does Past Performance Predict Future Returns?” in the Journal of Financial Planning; a highly useful summary of research findings.

Droms looked at every article published from 1990 in the three most highly ranked academic finance journals (Journal of Finance, Journal of Financial Economics, and Review of Financial Studies), plus every article referenced in the two most recent articles in each of the top-tier journals that deals directly with performance persistence. Many articles appearing outside of these journals were also included. Droms therefore made what could be considered a reasonable assertion that although some ‘small stones’ may have been left unturned, no stone in the top-tier finance journals was overlooked.

We are all used to seeing disclaimers and warnings along the lines of “Past performance is not indicative of future performance” placed on investment marketing literature, as dictated by regulatory bodies to protect the naïve public. However, the conclusions that Droms draws from the research do somewhat confirm what the lay investor feels intuitively. Some key findings include:

- The most important implication from performance persistence studies is that the historical performance of mutual funds contains useful information about future performance, at least for one-year holding periods. Winners in one year tend to remain winners in the following year and losers have an even stronger tendency to remain losers.

- The studies consistently find that investment strategies based on investing in portfolios of fund winners out-perform the average fund as well as portfolios consisting of fund losers.

- The studies also demonstrate that performance is more persistent within categories than relative to the overall market. International equity funds also show strong short-term persistence.

- Evidence for longer-term performance, such as two to four years, is much less clear; generally it’s not as strong as short-term persistence.

- There is some suggestion that persistence may be sensitive to the period tested. Thus, findings of persistence need to be interpreted with caution and should not be the sole or even the most important criterion for selecting a mutual fund.

Droms comments that: “These results tell us that historical performance can provide a useful screen to identify likely candidates for future investment as well as a list of likely candidates for avoidance or for sale if already held.”

Also: “But since those funds with excellent long-term performance almost always experience one or more years of sub-par performance, one year of below-average performance should not be the sole or even the most important criterion for selling a fund, but as a minimum it should serve to raise a warning flag and identify funds that should be reviewed for appropriateness.”

In fact, for a fund with an excellent long term track record, if all else is equal (for example, the fund manager has not changed) then depending on market conditions a below-average one-year performance could simply indicate the manager is being more cautious than most – not necessarily a bad thing if this is a core holding.

XIIC 2010

Returning to the question of the relative importance of asset allocation and active management, J.X.Xiong, R.G.Ibbotson, T.M.Idzorek & P.Chen published “The Equal Importance of Asset Allocation and Active Management” in the March/April issue of the Financial Analysts Journal.

This significant paper builds on and clarifies the work of Ibbotson & Kaplan (2000) as well as Hensel, Ezra and Ilkiw [HEI] (1991).

The paper attempts to answer the question, Why do portfolio returns differ from one another within a peer group? Or, put slightly differently, Is the difference in returns among funds the result of asset allocation policy or active portfolio management? XIIC decomposes a fund’s total return as follows: (i) the applicable market return, (ii) the asset allocation policy return in excess of the market return, and (iii) the return from active portfolio management. The goal is to address the relative importance of asset allocation policy versus active portfolio management.

The figure below illustrates the decomposition of total return variations under the different methodologies of BHB 1986 and of HEI 1991 and Ibbotson & Kaplan 2000.

XIIC used 10 years of return data (May 1999 – April 2009). They removed duplicate share classes and required that each fund have at least five years of return data. The final sample consisted of 4,641 US equity funds, 587 balanced funds, and 400 international equity funds. They estimated the asset allocation policy return for each fund using return-based style analysis (Sharpe 1992).

XIIC explains regarding time-series analysis: “As discussed earlier, one problem with the time-series analysis of total returns is that the results are dominated by overall market movement. To further analyse the relative importance of asset allocation policy and active management within a peer group, a more applicable approach is to use excess market returns instead of total returns as the regression variables for the time series.”

Regarding cross-sectional analysis: “Unlike time-series regressions, [..] cross-sectional regressions on total returns are equivalent to cross-sectional regressions on excess market returns. Cross-sectional regressions naturally remove the applicable market movement from the peer group, essentially resulting in the same analysis as using excess market returns. We reiterate this point because in most studies on this topic, researchers performed cross-sectional regressions on total returns and failed to recognise the natural removal of the applicable market movement.”

Because the market movement is naturally removed during the cross-sectional analysis, the resulting R-squared is an indication of the relative importance of detailed asset allocation versus active management after removing market movement.

XIIC presents results in three areas: a time-series regression on total returns, a time-series analysis of excess market returns, and a month-by-month cross-sectional analysis.

Time Series Regression On Total Returns

From all three fund universes, XIIC presents two important observations. Firstly, the market movement component accounts for about 80 percent of the total return variations and dominates both detailed asset allocation policy differences and active portfolio management. In other words, market movement dominates time-series regressions on total returns. This is consistent with HEI 1991 and Ibbotson & Kaplan 2000.

Secondly, XIIC found that excess market asset allocation policy return and active portfolio management have an equal level of explanatory power, with each accounting for around 20 percent. (The interaction effect is a balancing term and makes the three return components’ R-squared add up to 100 percent.)

Time Series Analysis of Excess Market Returns

A time series of portfolio excess market returns regressed against policy excess market returns explicitly removes the overall market movement seen in the total return regression, and is therefore more relevant for identifying the explanatory power of asset allocation within a particular peer group or universe of funds.

As seen from the above table, overall, excess market asset allocation policy and active portfolio management have about an equal amount of explanatory power after removing the applicable market effect.

Month-by-Month Cross-Sectional Analysis

With respect to cross-sectional analysis, XIIC defined the cross-sectional fund dispersion as the standard deviation of cross-sectional fund returns, and noted it was very volatile.

Taken together, XIIC confirms the widely held belief that market return and asset allocation policy return in excess of market return are collectively the dominant determinants of total return variations, but it clarifies the contributions of each. The rolling cross-sectional R-squared’s ranged from 0 percent to 90 percent, indicating that the dispersion changes over time and is period specific.

In conclusion, XIIC comments: “More importantly, after removing the dominant market return component of total return, we answered the question, Why do portfolio differ from one another within a peer group? Our results show that within a peer group, asset allocation policy return in excess of market return and active portfolio management are equally important.”

XIIC noted also that the relative importance of asset allocation policy returns in excess of market returns and active portfolio management is an empirical result that is highly dependent on the fund, the peer group, and the period being analysed.

REFERENCES & LINKS

H.M.Markowitz, “Portfolio Selection.”

The Journal of Finance, Volume 7, Number 1, March 1951, pp77-91

http://www.gacetafinanciera.com/TEORIARIESGO/MPS.pdf

G.P.Brinson, L.R.Hood and G.L.Beebower, “Determinants of Portfolio Performance.”

Financial Analysts Journal, July/August 1986, pp39-48.

Original reprinted in the January/February 1995 edition:

W.W.Jahnke, “The Asset Allocation Hoax.”

Journal of Financial Planning, February 1997, pp.109-113

http://www.buyside.co.uk/assets/pdfs/further_reading/the%20asset%20allocation%20hoax.pdf

R.G.Ibbotson and P.D.Kaplan, “Does Asset Allocation Explain 40, 90 or 100 Percent of Performance?”

Financial Analysts Journal, January/Februrary 2000, pp26-33.

W.G.Droms, “Hot Hands, Cold Hands: Does Past Performance Predict Future Returns?”

Journal of Financial Planning, May 2006, pp.60-66

J.Xiong, R.G.Ibbotson, T.Idzorek, P.Chen, “The Equal Importance of Asset Allocation and Active Management.”

Financial Analysts Journal, Volume 66, Number 2, 2010.